The concentrated rally in US markets this year isn’t out of the ordinary. Doubters would have you believe the market is on shaky ground with the rally being led by so few names. But the same prognosticators fail to recall that rallies following bear market recessions typically feature a concentrated move at the top before broadening out.

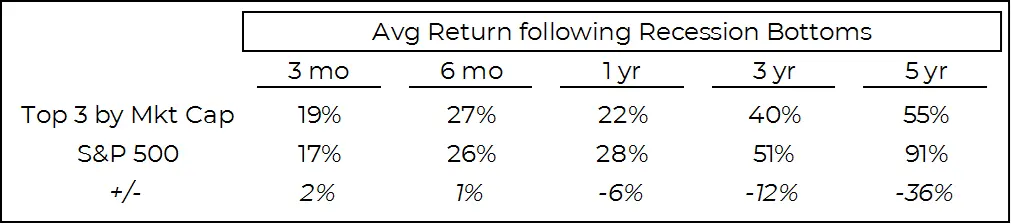

Going back to 1990, the top three names by market cap (i.e. the largest stocks in the S&P 500) outperformed the market three and six months after a recession bear market. In other words, the big names fair better than the rest coming off the bottom.

When the market is lowest, investors’ doubts and fears are highest. Taking a flyer bet on an unloved name isn’t something most have the stomach for so they stick with what worked before.

Why wouldn’t the market leaders continue to lead in the new bull market? Two reasons: first, sometimes the world changes and the companies and sectors best positioned to profit change with it. GE and Exxon come to mind. Second, valuations become hard to live up to for even the strongest companies. Take Microsoft, for example. The firm was one of the top stocks by market cap when the market bottomed during the dot com recession. Microsoft outperformed the broader index over the next 3-, 6-, and 12-months before falling behind. 3- and 5-year returns lagged by 4% and 17%, respectively.

Microsoft didn’t stop being a great company. It’s valuation just got too stretched to make it a good stock. With a trailing P/E of 61x at the end of 2001, Microsoft would have had to grow its earnings ~3+ times faster than the rest of the market to justify its price. That’s a lot to ask, even of one of the best companies of the last 30+ years.

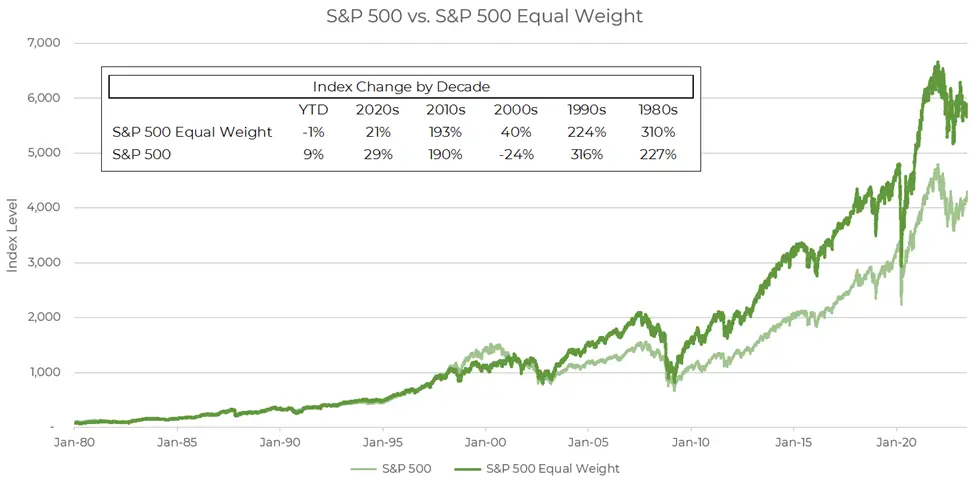

Another way of looking at this is by comparing the S&P 500 with the S&P 500 equal weighted index. The S&P 500 is weighted by market cap, which gives outsized influence to top stocks. For example, if company ABC is worth $5 trillion and the S&P 500 is worth $100 trillion, then company ABC would make up 5% of the index. ABC’s stock would influence the index more than a $1 trillion company making up 1% of the index. By contrast, an equal weighted index treats the largest stocks the same as the smallest stocks thereby neutralizing the influence of mega-cap stocks.

Comparing the S&P 500 with its cousin, the equal-weighted index, can give us a rough sense of market breadth.

With year-to-date gains going to the top names in the S&P 500, it’s no surprise that the equal weighted index has trailed. But we’ve seen this story before. During the 1990s, when excesses at the top of the market drove the index higher, the S&P 500 outperformed its equal-weighted cousin by a landslide. As market breadth normalized in the 2000s, the balance of power shifted from the best to the rest.

This is not a call to reallocate to an equal weighted index. But it does show that prudent, properly weighted diversification works in the long run even when a chosen few seem poised to leave the rest behind. History suggests upside gains are in store for the patient and prudent.

Data Source: YCharts